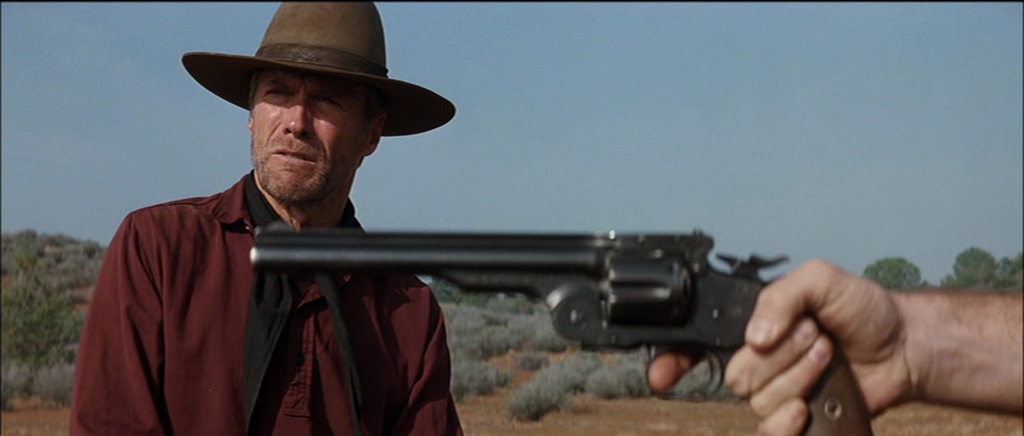

“I guess they had it coming…”

“We all got it coming…”

In Christian circles, that exchange probably rivals “make my day” or “do you feel lucky, punk?” as the most iconic piece of Eastwood dialogue. The irony of its status is that the doctrine that it embodies is one of the least popular doctrines in contemporary theology.

Whether arguments about it use phrases such as “original sin,” “total depravity,” or “predestination,” the assertion that all humans must be forgiven for something in order to be saved from damnation is deeply offensive to the modern assertions of humanism (secular or otherwise) that seek to explain evil only as the product of institutional failures and peer pressures.

I have long argued that Unforgiven only works as a spiritually significant cinema to the extent we are capable of and willing to read its title unironically. To the extent that William Munny (Clint Eastwood) really, truly believes his present deeds cannot atone for his past sins, the film can invite spiritual contemplations. If he cannot be forgiven, who can be? And if there is no hope for the humblest of sinners, what can there be for those who cling to the last vestiges of pride and self-righteousness?

Like another film on the Crime and Punishment list, The Godfather, Unforgiven is comfortable using terms such as crime and sin, punishment and damnation, interchangeably. But whereas the characters in The Godfather, especially Michael, rail against the hypocrisy of selectively labeling some of us criminals, Munny sees in the hypocrisy of others confirmation of the low view of human nature. Both films invite us to contemplate how little difference there is between those called saints and those called sinners, between those whose crimes are deemed worthy of punishment and those whose crimes are not-so-secretly idolized.

The closing scene that appears to echo the same sentiment is when Little Bill claims, “I don’t deserve this” and Munny retorts, “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.” Yet if we all have it coming, wouldn’t a more proper response be, “Yes, you do”? Perhaps this line indicates a slight but significant shift in Munny’s soul. He has gone from claiming all deserve death to claiming that being deserving is not the cause of our death.

The line indicts also indicts us, denying us the pleasures and reassurances found in the myth of redemptive violence. That is why doctrines of universal salvation are as unpopular to modern sentiments as those of original sin. We want to believe, we need to believe, that some deserve punishment. And the only way we can justify the desire for punishment for them and grace for us is by convincing ourselves that there is some meaningful, essential difference between us.

Is there?

Truthfully, I think the answer is “yes,’ but that difference lies not in which crimes Munny or Litle Bill have committed nor which of them did so under the cover of authority. Perhaps that difference is that one tries to do good, Not as penance. Not as atonement. One tries to live his life in such a way that it might honor the other who did not so much forgive him his trespasses as chose to love him in spite of them. — Kenneth R. Morefield (2024)

Arts & Faith Lists:

2004 Top 100 — Unranked list

2005 Top 100 — #100

2024 Top 25 Crime and Punishment Films — #7

2025 Top 100 — #59