This commercial dog is not going to ruin my Christmas.

A Charlie Brown Christmas premiered on CBS on December 9, 1965, and every year since, it has continued to welcome viewers into twenty-five minutes of the cool sounds of Vince Guaraldi’s music, the vivid colors of graphic blandishment (a term coined for Peanuts specials), and the charming diction of the child voice actors bringing the Peanuts characters to life. But along with the familiar holiday warmth, the television special also challenges us to find our way through the uneasy balance of the commercial and the spiritual in the Christmas season.

The origin of A Charlie Brown Christmas could hardly be more commercial. The production took shape under the guidance of a Madison Avenue ad agency, an international soft drink brand, and a national TV network. They all needed a Christmas special, produced from start to finish under an incredibly tight schedule, that would bring their companies success. The special was purpose-built to attract the audience that had delighted in Rankin/Bass’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer in 1964. Spiritual contemplation and biblical recitation were primary goals of no one but Charles Schulz, creator of the Peanuts comic strip, who wrote the script. Everyone else leading the creation of the special thought first of commercial victory over their competitors.

The special’s first viewers had no doubts that this was as commercial as anything on television. While people in my generation associate the annual broadcast with Peanuts-themed commercials for Dolly Madison treats, the version that aired in 1965 integrated commercials into the special itself. The opening ice-skating sequence concluded with Linus crashing into a billboard emblazoned with “Brought to you by the people in your town who bottle Coca-Cola,” and a text overlay during “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” at the end of the show proclaimed, “Merry Christmas from the people who bottle Coca-Cola.” (Similarly integrated advertisements for Dolly Madison joined the Peanuts specials the following year in Charlie Brown’s All-Stars. All of the sponsorship messages are now edited out of the specials.)

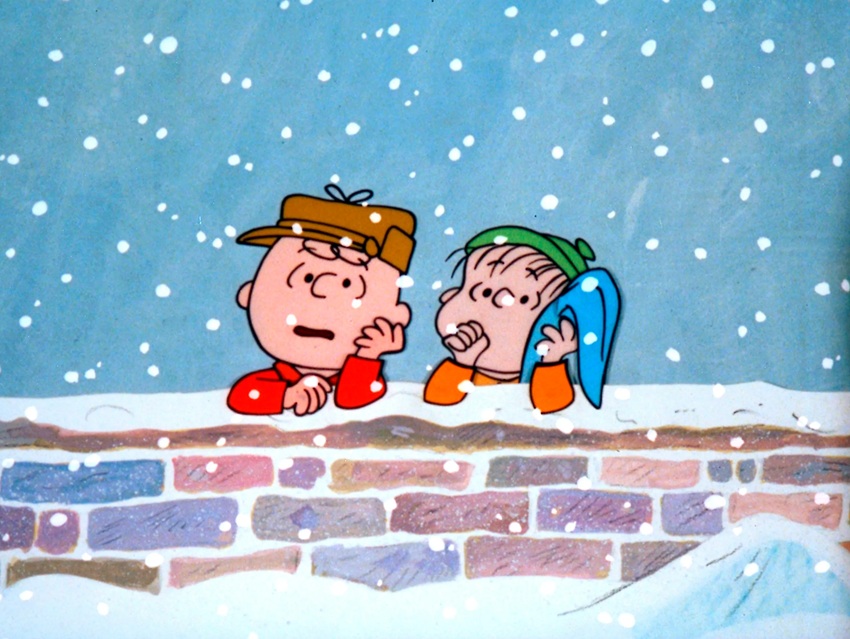

As the story opens, we find Charlie Brown overwhelmed by internal agitation. “Christmas is coming, but I’m not happy,” he confesses to Linus. “I always end up feeling depressed.” We chuckle at this existential dread from a young child . . . but we also understand. We want to know: Will this story subvert its own commercial premise and open a space for Charlie Brown to encounter the numinous? We need it to, because we need that for ourselves.

In response to Charlie Brown’s increasing frustration, other characters advise him to do (“You need to get involved in some real Christmas project”) and acquire (“Get the biggest aluminum tree you can find”). But he really yearns for a different way of celebrating Christmas. Eventually, in desperation, he cries out, “Isn’t there anyone who knows what Christmas is all about?” Linus walks to center stage, takes the spotlight, and reminds us of another way to commemorate Christmas: quiet reflection on the night it all started, before it grew into a commodified to-do list of activities and purchases. It’s a moment of reverent wonder that brings more comfort even than a trusty blanket. Charlie Brown didn’t know to ask for it—and often in the busyness of Christmas, neither do we—but we recognize it as perfect. For just a moment, the commercial gives way to the spiritual. In response to skepticism about the idea of animated characters quoting the Bible, Schulz insisted, “If we don’t do it, who will?”

The story that was nearly suffocated by the commercial culminates in the spacious openness of a winter night, stars sparkling overhead. The story that one individual shares with another individual grows to welcome a renewed community of friends singing the message of the angel choir on the first Christmas. Angst has given way to joy: “Joyful, all ye nations rise, join the triumph of the skies; with th’angelic hosts proclaim, ‘Christ is born in Bethlehem!’” But there’s a reason we need to watch A Charlie Brown Christmas again, year after year: We’re always in danger of forgetting its lesson. This special reshaped its commercial origins to celebrate the real meaning of Christmas, but it risks being re-commercialized, a product that we can put on our shelf and enjoy as a comforting possession. You can “own” A Charlie Brown Christmas as pajamas, playing cards, cookies, coloring books, and endless reissues of Guaraldi’s soundtrack. This is our ongoing need for the special. As many times as we watch it, it continues to call to us: Here’s an opportunity for an encounter with the spiritual. Will you hold onto it and refuse to let it (and the Christmas season) become a commercialized, commodified ritual? — Neil R. Coulter (2025)

Arts & Faith Lists: