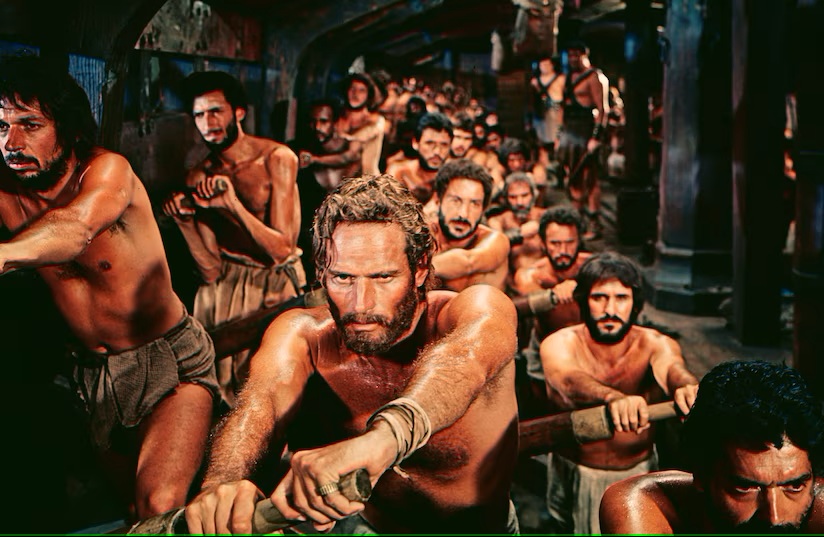

Ben-Hur is a glorious example of epic Hollywood filmmaking—big, bombastic, sometimes creaky and often inspiring. It combines the usual ahistorical Hollywood hokum (“Roman salutes,” slave galleys, stately white marble) with an epic story that’s more Alexandre Dumas than the Gospel of Luke. A young man, betrayed by his former friend, is sold into slavery. He wins his freedom and makes his fortune before returning to his home to confront this friend and enact revenge. Call it The Count of Mount Jerusalem.

And yet, the movie, based on a novel by Lew Wallace, has moments of grace (both quiet and bombastic) that point beyond its melodramatic Hollywood exterior. It accomplishes this through a number of mirroring details. Most obvious is the moment where Ben-Hur is given water by a silent Jesus, a moment mirrored later in the movie when Ben-Hur himself gives water to the suffering Christ. Divinity and humanity minister to each other. At another point, Ben-Hur rejects Roman citizenship. Rome in this movie is a totalitarian state which demands obedience from everyone. Ben-Hur refuses that control. But he acts out of anger; his hope is that he land of Judea will be washed in the blood of the conquering Romans. And, indeed, at the end of the movie the land is washed in blood—the blood of Jesus, blood that heals the sick and promises a future redemption from the control of Rome. The bloodshed that threatens the might of the Roman empire is not the blood of violence but the blood of sacrifice.

All of this is accomplished without the Christ mentioned in the subtitle ever speaking or showing His face. Indeed, the movie may lay itself open to accusations of soft-pedaling from the more doctrinally-inclined; we are told that the message of Jesus is that God is in everyone (rather than located in the person of the Roman emperor), that his message is a non-confrontational one of loving enemies. This might strike one as generic midcentury civic religion. But these words are hardly toothless; in the context of the story of Judah Ben-Hur—and in the Dumas-inflected revenge narrative that forms the spine of the movie—they become a striking rebuke to the audience’s generically-informed expectations. Revenge will only lead to more suffering; hatred can only breed hatred, even if that hatred is directed toward the monstrous evil of Rome.

Tellingly, the movie ends before the resurrection of Jesus. It is not that there is no space in the world of Ben-Hur for a physical resurrection, but the movie is more interested in other things. The true resurrection, the essential one for this movie, is the resurrection of Judah Ben-Hur. Given the overwhelming might of Rome, what can someone in Ben-Hur’s position do? Rebellion is an option, but if Rome can destroy someone like Jesus (who is presented in the movie as a wholly unthreatening figure), it will not hesitate to destroy Judah Ben-Hur. He can continue to throw himself against the bars of his Roman cage, gnashing his teeth and thrashing about, but ultimately it will be fruitless. The movie offers an alternative: sacrificial love and a focus on those close to him. On recounting the words of Jesus asking God to forgive His killers, Ben-Hur says “I felt his voice take the sword out of my hand.” The movie ends with Ben-Hur embracing his mother and sister, being joined by his beloved, Esther. The final shot, then, is of the empty cross. The message is clear: He is not dead; He is risen in the hearts of His followers. Where there is love, He is there, and the might of the Roman Empire can never crush this love. — Nathanael T. Booth (2025)

Arts & Faith Lists: