The 1970s marked a major turning point for the life and work of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa, as the guardedly hopeful portrayals of individual and communal transformation seen in many of his postwar films culminated in his final black-and-white movie, Red Beard (1965). His next four films, including Dersu Uzala (1975), are by contrast the work of a disillusioned man, depicting societies and people powerless to halt inhumanity and the tragic march of modernization.

This major tone change coincided with his own existential suffering; facing numerous personal and professional hardships, Kurosawa attempted suicide in 1971. Subsequently failing to obtain domestic financial backing for a new movie, and rejected by a new generation of Japanese film directors, he accepted the offer to direct Dersu Uzala, a Soviet-funded project based on the diaries of Russian explorer, Vladimir Arseniev.

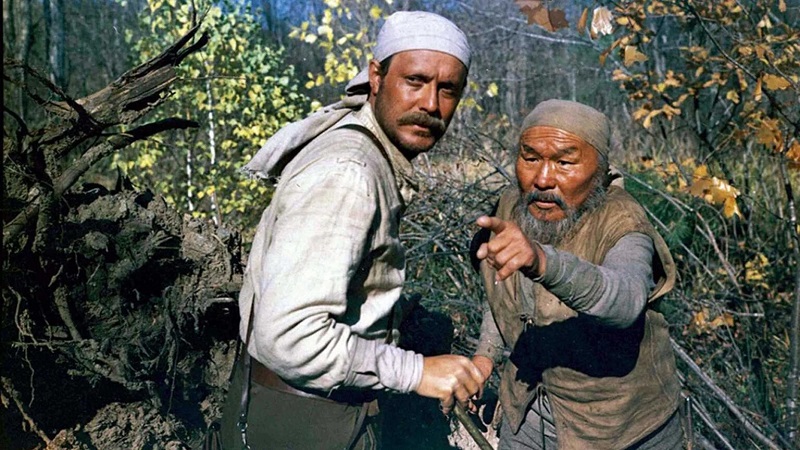

Dersu begins in 1910, with Arseniev searching for the grave of the title character in a newly-populated region of Siberia. The story rapidly jumps back in time to 1902, when Dersu—a solitary, nomadic hunter—happens upon Arseniev’s surveying party in the Siberian wilderness. The film then follows the deepening relationship and spiritual kinship of these two lead characters over the next several years. Dersu proves a superb guide for the expedition, and while the Russians initially view him with condescending amusement, they come to admire this man with “a beautiful soul” (Arseniev’s description) whose altruism and animistic beliefs allow him to live harmoniously in his wild surroundings.

The product of several months of on-location filming with an all-Soviet cast in Siberia, Kurosawa effectively uses his trademark long range lenses in Dersu Uzala to reveal wide natural tableaus in which the human figures are often silhouetted miniatures in massive landscapes. Kurosawa always excelled in depicting violent turns of weather, and here we see windswept plains that can quickly claim lives with their brutal chill. And although Dersu is only his second color film, he masterfully captures deep-red sunsets coloring broad fields of ice, ominous moonlit nights, summery forests, and ice-clogged rivers. With such immense vistas, violent movement, and intense color, it may be argued that Nature is actually the main character in this film.

Sadly, through his continued dealings with the surveying expedition, Dersu alienates the spirits of Nature, such that he can neither continue to thrive in the wild nor adapt to urban life. Inevitably, in Kurosawa’s tragic vision, both Dersu and Nature are powerless to flourish in the twentieth Century; the exiled director shows us the exiled ideal man. — Andrew Spitznas (2010)

Arts & Faith Lists: