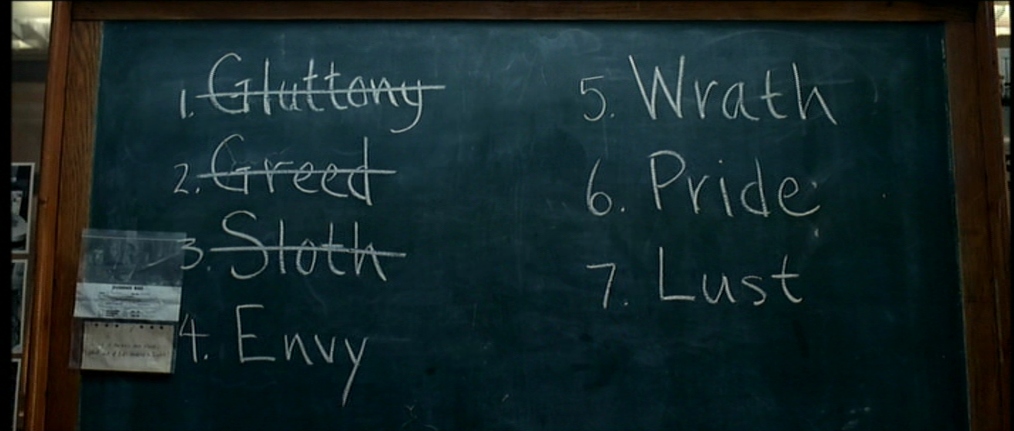

Pride. Greed. Wrath. Lust. Envy. Gluttony. Sloth. The Seven Deadly Sins.

It has been almost thirty years since David Fincher’s Se7en was released in movie theaters

around the globe, and yet it is still reigns supreme as one of the greatest serial killer movies of all time, not only because of humanity’s morbid fascination with murder en masse but also because the film speaks to the spiritual ethics surrounding this morose obsession.

There is no doubt that, on the surface, Se7en can be misconstrued as a moody commonplace police procedural; however, the film cuts deeper into the souls of its viewers by exposing the carnal instincts we all have and are capable of acting on, which can lead to an apathetic, sinful bloodlust, which is inherent within all of us whether we like it or

not.

The film stars Morgan Freeman and Brad Pitt as Detectives William Somerset and David Mills (respectively), who are on the hunt for the allusive “John Doe,” who kills and, at times, tortures victims whom he feels are guilty of said deadly sins. “Doe” force-feeds an obese man until he almost explodes. He brutally murders a high-priced, corrupt defense attorney. He chains up a drug-dealing pedophile and keeps him alive until he is nothing but a stinking, screaming bag of bones. The list goes on, and viewers are forced to see the aftermath of these gory crimes, experiencing the darkness that Somerset and Mills are experiencing throughout, up until the film’s unexpected and masterful conclusion (“What’s in the

box!?”).

Somerset, the almost-retired veteran, is logos. Mills, the newbie, is pathos. And, “Doe,” in the

sickest of ways, is ethos. Throughout Se7en, there is certainly a fight between good and evil, a common trope in neo-noirs such as this one; however, there is also a distinct push-pull between logic and emotion, which makes viewers question the concept of ethics. Is “Doe” doing God’s work? Is there a logical, methodical agenda to what he is doing? Or is “Doe” just a nut-bag, as Mills suggests? What the audience learns is that it is all just not that simple. Yes, the good guys can catch the bad guys; however, who are the good guys and who are the bad guys, really?

And, this is what ultimately brings us to the spiritual/religious nature of Se7en. This is why the film is so meta and so timeless. Who judges whom? Should we be casting stones? Viewers enthusiastically watch individuals like “Doe” regularly in a variety of mass-mediated ways. That is why true crime is marketable and pervasive. By the end of David Fincher’s film, it quickly becomes hard to tell what is sinful and what is not; and, more importantly, who is sinful and who is not? Se7en, thus, is not just a genre picture; it is a mirror that forces us to see ourselves, however distressing that may be. — Douglas C. MacLeod, Jr. (2024)

Arts & Faith Lists: