Few religious dramas have been met with as much contention and protest as Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. Based on the 1955 novel by Nikos Kazantzakis, the film’s unorthodox portrayal of Jesus Christ (Willem Dafoe) and his battle with various forms of temptation proved to be an uncomfortable experience for Christians upon release, and still faces censorship in various countries around the world.

But, as with any film “based on a true story,” one shouldn’t always expect textual or factual purity, but instead an adaptation meant to convey something new. Through that lens, The Last Temptation of Christ reveals itself to be a film full of spiritual musings on purpose, grace, love, and yes, temptation.

The uniqueness of Last Temptation begins with its presentation. Its shot simplicity and intimate scale are more evocative of neorealist films like The Gospel According to St. Matthew (one of Scorsese’s cited influences) than traditional biblical epics. Miracles and the supernatural are shown simply, like an apple seed instantly becoming a tree, presented as signs that God is all around us.

In a similar vein, Scorsese and writer Paul Schrader deliberately avoided the elevated, poetic language often found in classic films like Ben-Hur or even most translations of the Bible. Instead, The Last Temptation of Christ uses conversational language to create a sense of modernity and relatability. While this decision may seem arbitrary to viewers in 2025, it’s fascinating to hear Christ and his disciples speak in the modern vernacular a full five years before the popular Message bible translation was released in contemporary English in 1993.

Verses like John 10:16 (“And other sheep I have, which are not of this fold: them also I must bring, and they shall hear my voice; and there shall be one fold, and one shepherd.”) are spoken here with simplicity and directness: “You think God belongs only to you? He doesn’t. God belongs to everybody, to the whole world.”

This particular line of dialogue speaks volumes to the intention behind Last Temptation’s modernization of the Bible. “Christ’s teachings are about all of us,” Scorsese explains, “the secure and the insecure, the powerful and the powerless, the down and out, the addicts, the people in real pain, the people caught in states of delusion, the ones who feel absolutely hopeless and see no possibility of grace or redemption.” Since Christ came for everyone, it only stands to reason that his message should be delivered in a way that everyone could understand.

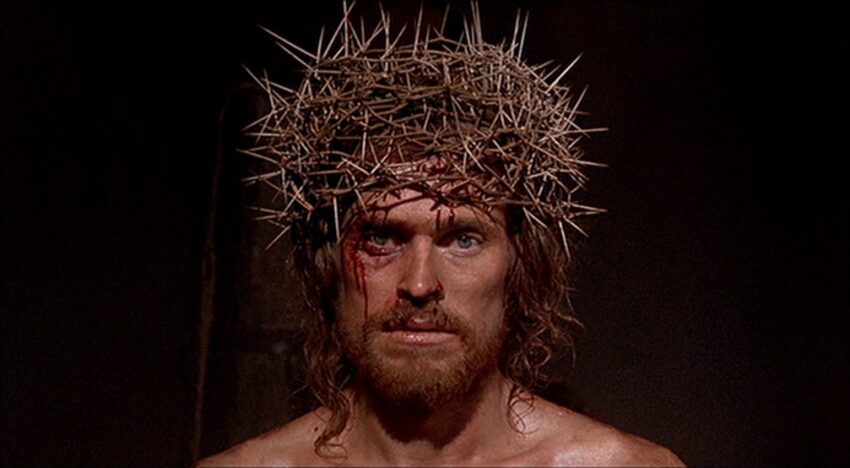

Willem Dafoe may seem an unusual choice to play the Son of God, but just as Scorsese eschews filmmaking choices associated with biblical epics, Dafoe’s rugged, relatable, and down-to-earth portrayal of Jesus pairs perfectly with the colloquial dialogue and intimate settings. There’s an everyman quality to his performance that stands out amongst traditionally stoic or mystical takes on Christ in film.

But, of course, that brings us to the story’s controversial portrayal of Jesus at large. Last Temptation focuses intensely on Christ’s humanity, internal struggles, and doubts, presenting him as a character grappling with the enormity of his role in salvation.

“The film could be faulted for overemphasizing the humanity of Jesus as opposed to the divinity of Christ,” reflects Schrader. “But maybe it’s a healthy sort of counterbalance to a lot of Christianity which tends to push aside the human elements and just focus on the more glorious…elements.” If Christ was both fully human and fully divine, then the filmmakers saw it as their duty to ensure that his humanity was a point of emphasis.

In this way, the film is both an internal and external battle between the human and the divine, part of the burden of Christ’s messianic role. How is it even possible for someone to equally inhabit both? That question leads to a surprising discovery. The antagonist of the film, according to Schrader, is God.

It’s wise to remember that calling God the antagonist is not the same as calling him the enemy. But in a film where Christ is shown at his most human, it only makes sense that God Himself, dwelling in Christ, is the opposing force. Said another way, divinity is put in direct contrast with humanity, making Christ’s existence as both a sort of oxymoron. It’s this seeming incompatibility that the film’s characters struggle to understand, and that Christ himself grapples with. And, of course, it’s these disparate qualities that Satan uses to tempt Christ.

So what is the “last temptation” that Christ deals with? It’s a metaphorical extension of his time in the Garden of Gethsemane, his plea with God to take the cup away and to find another way to save mankind. And Satan plays on these thoughts and fears, telling Christ, “What arrogance to think you can save the world. The world doesn’t have to be saved: save yourself.”

In essence, the greatest temptation here is to just give up, what Scorsese calls “spiritual exhaustion.” The feeling of “I guess this is all there is, so I might as well grab as much of it as I can.” And so Christ is tempted with the chance to walk away from his role as Messiah and to simply live his life out as a human.

And, shockingly, it appears that he succumbs to this temptation. He comes down from the cross and lives out his life, even marrying Mary Magdalene. But as He nears the end of his life, Christ realizes this too, was all a temptation. The final temptation. In a moving and emotional turn from Dafoe (mirroring Christ’s cries in the garden), He begs God to let him fulfill his purpose and die for humanity. At this point it’s revealed to the audience that Christ never left the cross. The temptation had all played out in his mind, but he resisted.

The beauty in Scorsese’s film—the extended temptation sequence, the colloquial dialogue, the overly humanized portrayal of Jesus—is that the Jesus portrayed here abundantly understands, loves, and empathizes with humanity, more than perhaps any other film version of Christ. He is saving humanity not only because of a calling or destiny, but because he understands their very essence, their desires, their temptations. And in spite of that—or really, because of that—he chooses to sacrifice himself for us.

“Remember, we’re bringing God and man together,” Jesus says in the film, “They’ll never be together unless I die. I’m the sacrifice.”

This portrayal of Jesus, the abundantly (perhaps over-abundantly) human portrayal, realizes that his dual identity as fully God and fully man is what makes Him the only one capable of humanity’s salvation. God and humanity can only be united by someone that represents both God and humanity.

By film’s end we’re left not with a blasphemous rejection of Christianity, but with the ultimate story of overcoming temptation, choosing God’s will over one’s own. God’s sovereign plan, the one that Jesus was tempted over and over again to reject, could not be driven away or defeated. That’s the power of Christ’s last words in the film: “it is accomplished.”

Christian Jessup (A Cloudy Picture), 2025

Arts & Faith Lists: