L’Avventura (1960) has long been known as the first feature in Michelangelo Antonioni’s “alienation” trilogy, which includes La Notte (1961) and L’Eclisse (1962). Yet the term “alienation” is too simple and too succinct a descriptor; this film is about emotional, social, and spiritual enervation, about something nightmarish. The inhabitants of Antonioni’s post-industrial, post-war West are profoundly sick, dysfunctional, wayward, and even pitiful, as he described them in a 1961 interview. Antonioni also remarked that “Eros is sick; man is uneasy.” A prevalent and vulgar form of eroticism took the place of more meaningful human forms of intimacy and connection, of work, and of spirituality. Even when the characters in the film try to connect, they largely fail. Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) begins an affair with Claudia (Monica Vitti) not long after his fiancee, Anna (Lea Massari), goes missing, and efforts to find her prove futile. Sandro suggests to Claudia that they should marry; her simple response is, “why are you asking me?” Claudia’s question recalls one that Anna posed to Sandro earlier in the film: “are we able to understand each other?”

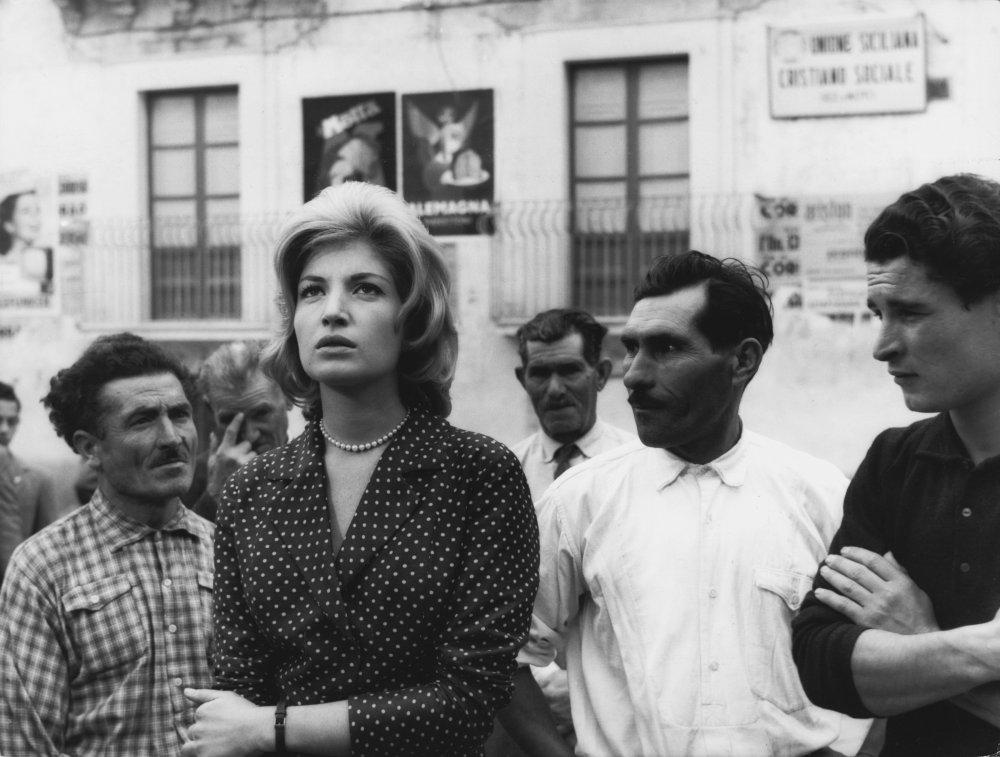

While in the city of Messina, searching for Anna, Sandro gets caught up with a massive crowd of men running after Gloria Perkins (Dorothy De Poliolo), an actress, writer, and call girl whose dress has a tear in it. In the town of Noto, as Sandro slips into a hotel to inquire about Anna, Claudia, remaining outdoors, becomes subjected to the ogling gazes of strange men who encircle her or peer down at her from balconies and staircases. Antonioni remarked in that 1961 interview that vulgar eroticism “is a symptom of the emotional sickness of our time.” Yet, in L’Avventura, he deliberately avoided offering any concrete solution to the emotional and spiritual emptiness that embattled his characters; their own lack of self-awareness is a critical part of their condition and disability. In the least, however, Claudia progresses far enough to offer a consoling, if uneasy, hand to the top of Sandro’s head as he sits quietly on a bench, sobbing. Crying is perhaps the only appropriate response to the dire atrophying of his humanity.

The characters’ poverty is social, interpersonal, emotional, not economic; they are, after all, members of the idle bourgeoisie. In this manner, Antonioni had turned against some of the core motifs of Neo-Realism, which often emphasized the quotidian lives of working-class men and women. With L’Avventura, he also departed from traditional narrative form, subordinating explanatory dialogue and the clear delineation of events to images, to the ways in which his actors occupied space within the frame, and to the characters’ relationships to their physical environment, especially architecture. This method requires viewers to work to interpret the characters’ states of mind by carefully examining their position within any given shot. The film scholar Robert Kolker, writing nearly forty years ago, aphorized that Antonioni “invents images rather than records them.” Put more aptly, Antonioni’s visual compositions themselves bear “the meanings of great importance.” Following Kolker’s lead and their own experience of the film, critics over the years have concluded that Antonioni created an entirely new visual grammar. Perhaps. Yet for all of his cinematic and narrative revisionism, for the direness and fear that inhabit this film’s story, and for all of Antonioni’s formalist attention to line and detail in his shots, L’Avventura is stunning largely because of Antonioni’s keen eye for the picturesque, for creating viscerally beautiful images: two lovers kissing against the backdrop of an ancient and desolate landscape; Sandro and Claudia debating the idea of marriage while navigating their way between enormous church bells and ropes that separate them as they talk; or Claudia, upon waking from sleep, opening the shuttered window of a small cabin to reveal a windswept sea and a brilliant sun rising on the horizon.

— Michael S. Smith

References:

Marga Cottino-Jones, Michelangelo Antonioni: The Architect of Vision. Writings and Interviews on Cinema. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996)

Robert Philip Kolker, The Altering Eye: Contemporary International Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983)

- Directed by: Michelangelo Antonioni

- Produced by: Amato Pennasilico

- Written by: Michelangelo Antonioni Elio Bartolini Tonino Guerra

- Music by: Giovanni Fusco

- Cinematography by: Aldo Scavarda

- Editing by: Eraldo Da Roma

- Release Date: 1960

- Running Time: 144

- Language: Italian

Arts & Faith Lists:

2020 Top 100 — #45